What stories live in our bodies? As part of my graduate research I recently did a literature review on body mapping, a therapeutic art practice which has been used for embodied research amongst many different groups including new teachers, undocumented workers, people living with HIV AIDS, music students and more. The goal of these studies varied but throughout to understand peoples lived experiences and embodied knowledge. This research inspired me to create the guided project Mapping the Body’s Landscape so I thought it may be interesting to share what I learned in a blog post.

What is Body Mapping?

Body mapping involves drawing or painting an outline of the body and using symbols, color, imagery, and written words to explore personal experiences, emotions, memories, and identity within it. In my research I explored academic uses of these body maps in group settings aimed to explore embodied knowledge, often in communities navigating identity or faced with systemic oppression.

This is the research which inspired me to try body mapping myself and to listen more deeply to my body’s signals. I noticed the more I did this practice, the more attuned I became to my own boundaries and sensory needs in daily life as well as an ability to connect more deeply with peers.

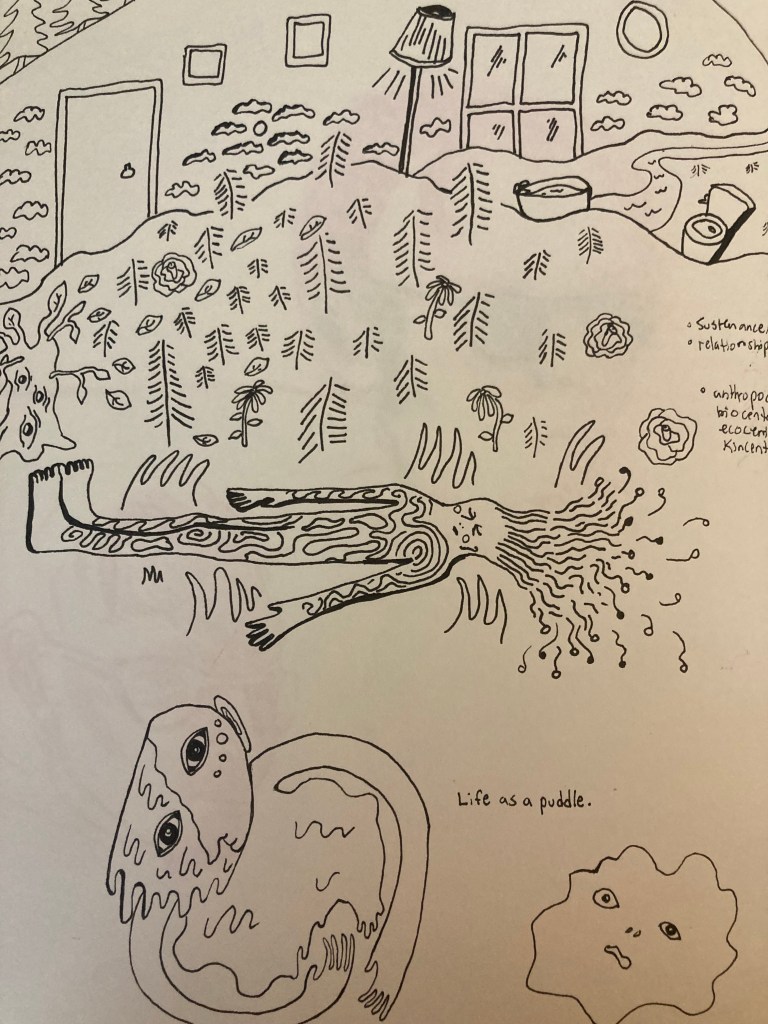

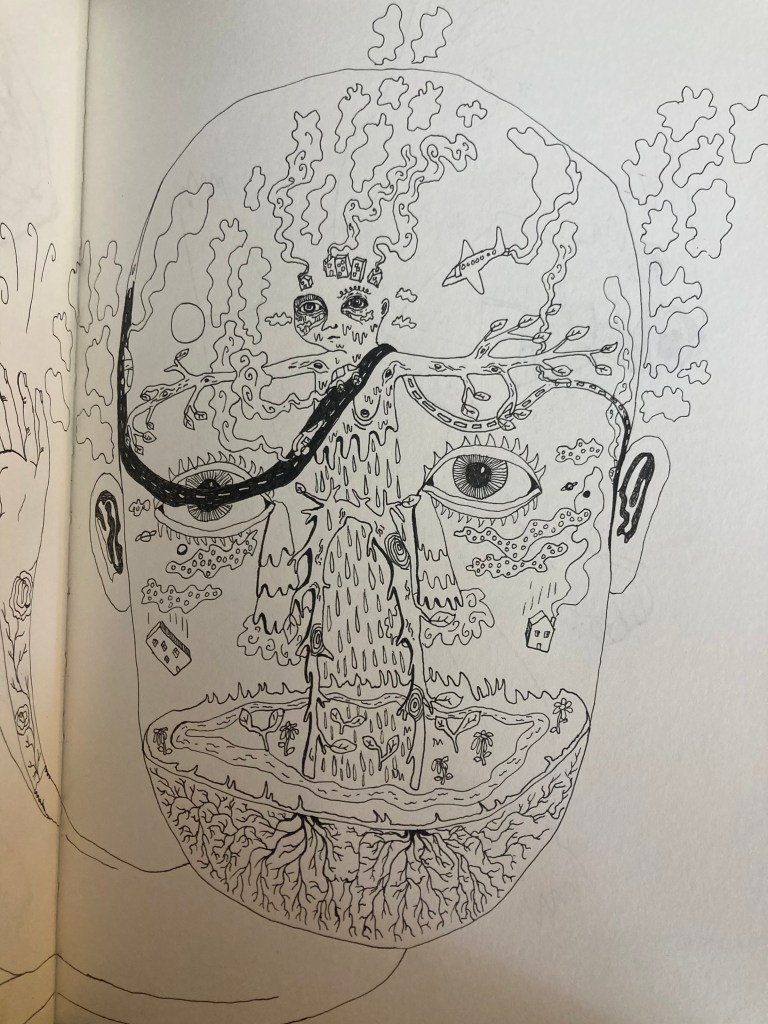

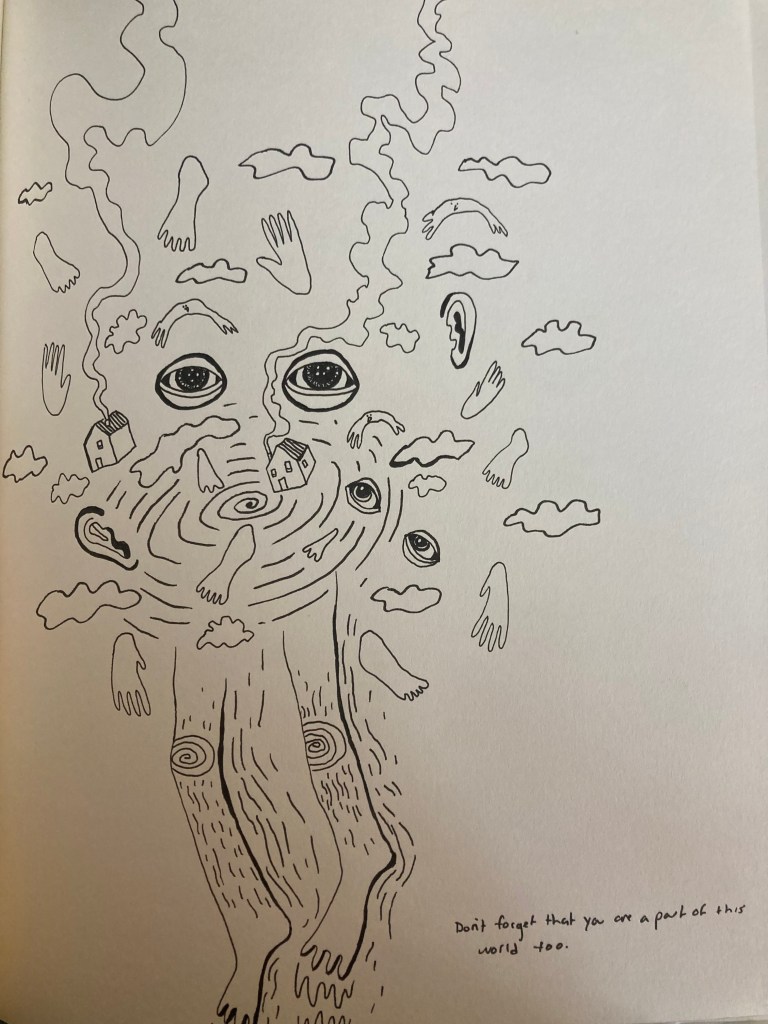

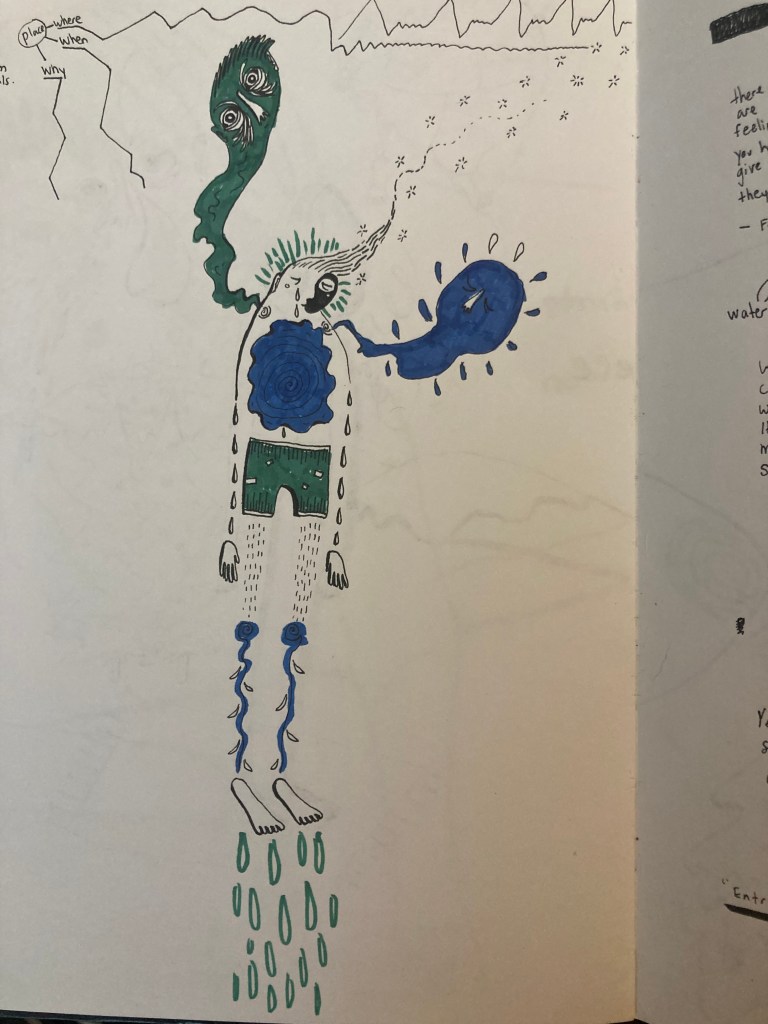

I also realized that I had been using body mapping in my drawing practice for years now to self soothe while experiencing big emotions or processing changes. Looking at some of these drawings from my undergraduate years I can see how I unconsciously began using this practice:

What is Embodied Knowledge?

In school we read, write and intellectualize the oppression and violence inflicted through systems of power, yet we are rarely taught how to identify or transform this knowledge within our own bodies. “Embodiment” as a term is common in therapeutic and academic settings which describe how we express our body’s awareness of the senses, memorize and histories. Most of the papers I found on body maps allude to Merleau Ponty’s philosophies of embodiment which unravel ways in which western institutions have commonly thought of the body as multiple distinct parts rather than as holistic beings. I less often I see these academics exploring how “embodied knowledge” is already evident in indigenous ways of knowing.

Embodied Learning is Not New

While I did a literature review of academic research, I think it’s important to note that the same capitalist illusion of endless growth applies to academic notions of “progress”. The colonial structures that have oppressed Indigenous knowledge systems have oppressed embodied learning of all peoples for ages – embodied learning is not new.

Leanne Betamosake Simpson’s paper Land as Pedagogy really changed how I understand knowledge. She shares how Anishnaabeg knowledge is lived through the body and community relationships, not just something to be thought about or discussed conceptually. Anishnaabeg knowledge is grounded in the interactions people have with each other, the land, and their cultural practices.

“Answers on how to re‑build and how to resurge are therefore derived from a web of consensual relationships that is infused with movement (kinetic) through lived experience and embodiment. Intellectual knowledge is not enough on its own.”

So I would like to acknowledge that there is contradiction in researching embodied knowledge within an instituions which has historically and continues to oppress embodied ways of knowing. I am drawn to body mapping because it seems to center body awareness, in a way I have found lacking in much of my education, but there is much to consider. I hope in my research I can offer it as a way to explore what it means to hold awareness, understand our stories, relate to each other and be grounded in reciprocity and accountability to where and who we live with.

How Body Maps Develop Body Awareness

The first most obvious benefit of body mapping, is developing body awareness. By visually representing the body, we can begin to access sensations, emotions, and needs that live beneath our conscious awareness.

In the study Body-Map Storytelling as Research (Gastaldo, 2012), researchers worked with undocumented workers in Canada to explore their health and working conditions. Participants were invited to map their experiences through prompts like body posture, physical marks, color, and their migration journey. One woman chose to depict herself in a fetal position, writing:

“Looking at my body in this position, I see a peaceful, restful person, and wish I could have just a third of such peace… People who work as hard as I do deserve to rest and feel in peace.”

Her map gave form to something deeply felt but perhaps difficult to attain: a yearning for rest.

Another example comes from a study by Constance E. Barrett (2006), where a violinist was struggling with her bowing technique. When she created a body map, her teacher noticed she had mistakenly mapped her elbow in the wrong place, higher than its actual location. Once corrected, her body adjusted, and the movement suddenly made sense. As Barrett notes,

“If there is a conflict between the way the body is mapped and the way it actually is, people will behave as if the map were true.”

Both stories show how body mapping is not just expressive but informative. It helps us see ourselves more clearly.

How Body Maps Tell Stories Through Symbols

In one study, Carolina S. Botha (2017) asked preservice teachers to create body maps of both a “super teacher” and a “villain teacher.” The results were interesting: one group drew their villain teacher with a mask, symbolizing someone who hides their true self. Another group’s “super teacher” had no face at all, expressing the idea that she plays many roles: teacher, mother, psychologist, and friend. Interestingly, both the hero and the villain lacked faces, pointing to the complexity in the groups understanding of teacher identity. As the groups discussed their choices, conversations unfolded around what qualities really make a good educator. In this way, the metaphors in their maps didn’t just reflect their beliefs, they deepened them.

Symbolism was also a key part of the LongLife Project, which worked with South African women living with HIV/AIDS. One participant represented her illness with a storm, writing:

“If a storm comes there is heavy rain, thunder, storms, lightning and wind. I represent HIV like that.”

Her imagery captured not only her physical symptoms, but also the emotional turbulence of her experience, which words wouldn’t be able to hold.

In the Adolescent X Project, youth of color were invited to map life experiences onto their body maps and then share them in story circles. Each participant created a legend: a visual guide of good and difficult moments. And then used it to map how they understood gender. For young women in the group, gender often emerged in symbols relating to harassment; for many of the young men, it surfaced as pressure to suppress emotion or perform masculinity. These maps made visible the unspoken narratives their bodies had been holding.

By engaging with symbol, metaphor, and story to express lived experience participants were able to articulate cultural pressures which might be more difficult to explore through words alone.

Relationship and Reciprocity

Again and again in the research I reviewed, participants formed quick, supportive relationships through the shared act of mapping their stories.

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, writing about Nishnaabeg knowledge systems, expresses how knowledge is relational and grown through webs of care and interdependence. She writes that Nishnaabeg knowledge is “not decontextualized knowledge,” but something rooted in compassion and difference (Simpson, 2014).

In the Adolescent X Project, for instance, a group of youth created body maps and then shared them in story circles. As they opened up about their identities, they recognized pieces of themselves in each other. In their compassionate noticing of similarities and differences between each other they began collectively brainstorming how to resist injustice, and care for one another. The body maps became a space for deep empathy and then solidarity with each other.

Anither example of relational and reciprocal learning through the use of body maps comes from a study by Treena Orchard (2014), where women living in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside created body maps to share their lived experiences. They later chose to display some of their work in a public art show, with t-shirts, brochures, and postcards. The women chose how their stories would be shared, and in doing so resisted city narratives of the downtown Eastside which aimed to gentrify, and neglect the homelessness crisis.

Body mapping, in these settings creating space for vulnerability, and also empowerment and solidarity in communities facing oppression.

Body Maps Show How Embodied Knowledge is Tied to Place

When you stop thinking categorically, it begins to feel obvious that the knowledge held in our bodies is deeply connected to place. Land, ecology, ecosystems, weather patterns. It also makes sense that the more disconnected we are from the land we live on, the more disconnected we might be from our bodies.

In mapping the body, we are not just marking where emotions live but also mapping how our bodies occupy space, belong (or don’t belong), and relate to the land around us.

In one example, researcher Helen Harrison (2021) used body mapping to compare her experience as a teacher and as a learner. In her “learner” body map, she drew intestines in knots over her abdomen, representing a physical tension she hadn’t fully understood. Upon reflecting, she recalled an experience of being unfairly failed by a teacher for yawning in class during a period of sleep deprivation. The discomfort in her gut as a learner was tied to her embodied memory of place: a school system where she felt unseen. The map gave her language to explore her own agency and lack of it within institutional spaces.

In another example from Body-Map Storytelling as Research (Gastaldo, 2012), undocumented workers in Canada mapped their migration stories through body-based imagery. One participant shared her body map with “big smiles” near her hands as symbols of hope that she would soon return home to reunite with her children. Although physically located in Canada, her body still carried an emotional belonging elsewhere, tied to family and homeland. Another participant used light blue to outline his body, representing the calmness he felt in Canada.

These stories show how body mapping can make visible the way our identities, memories, and aspirations are deeply tied to the land and the spaces we move through.

The Ethics of Using Body Mapping as an Educational Practice

As an art educator I am really interested in how I can bring “embodied learning” and body mapping into art projects. However there are still questions I am navigating when it comes to this. While researching the ethics and implications of body mapping these are the questions I am left with:

In a classroom setting, how am I handling confidentiality, especially when participants are sharing sensitive or personal stories?

What power dynamics exist between me and students as an educator? How do I address them with care?

Is the setting I’m working in aligned with the values of embodied learning or could it be reinforcing colonial or disembodied norms?

Am I honouring the origins and deeper context of the practices I’m using or am I simplifying or extracting from them?

Would this work look or feel different if it were held in a community-led, non-institutional setting?

Thats All For Today!

Thanks for taking the time to explore this with me. If you’d like to support what I’m doing, engaging with the content I’m creating by liking, subscribing, sharing or even sending a email message to me really motivates and inspires me to continue! I appreciate you all!

♥️

References

Barrett, Constance E. What Every Musician Needs to Know About the Body: plan for incorporating body mapping into music instruction.

Botha, Carolina S. Using Metaphoric Body Mapping to encourage reflection on developing identity of preservice teachers, South African Journal of Education, Volume 37, Number 3,August 2017.

Brodyn, Adriana. Lee, Soo Young. Futrell, Elizabeth. Bennett, Ireashia. Bouris, Alida.Jagoda, Patrick. Gilliam, Melissa. Body Mapping and Story Circles in Sexual Health Research With Youth of Color: Methodological Insights and Study Findings From Adolescent X, an Art-Based Research Project, Society for Public Health Education, 2022.

Drummond, Ali. Embodied Indigenous knowledge protecting and privileging Indigenous peoples’ ways of knowing, being and doing in undergraduate nursing education.

Gastaldo, D., Magalhães, L., Carrasco, C., and Davy, C. (2012). Body-Map Storytelling as Research: Methodological considerations for telling the stories of undocumented workers through body mapping. Retrieved from http://www.migrationhealth.ca/undocumented-workers-ontario/body-mapping

Harrison, Helen F . Body Mapping to Facilitate Embodied Reflection in Professional Education, Embodiment and Professional Education 2021.

Loftus, Stephen. Embodiment and Professional Education, 2021

Orchard, Treena; Smith, Tricia; Michelow, Warren; Salters, Kate & Hogg, Bob (2014). Imagining adherence: Body mapping research with HIV-positive men and women in Canada. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 30(4), 337-338.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake, Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 2014.

Solomon, Jane (2002). “Living with X”: A body mapping journey in time of HIV and AIDS. Facilitator’s Guide. Psychosocial Wellbeing Series. Johannesburg: REPSSI.

Stole, Stephen A., Thorburn, Malcom. Where Merleau Ponty Meets Dewey: Habit, Embodiment and Education, 2023.

Reihana, Tia. Place as the Aesthetic: an Indigenous Perspective of Arts Education. International Journal for Research in Cultural, Aesthetic, and Arts Education. Volume 1 (2023